|

'Sit The Horse Onto The Bit'

by Richard Weis

Photos by Alois Muller

Reproduced from Dressage Today

Richard Weis has drawn record

crowds at the German Olympic Training Centre by giving top European dressage

riders new tools to gain a more effective seat. Inspired by a phrase from

a German text, the work has become his passion and his life.

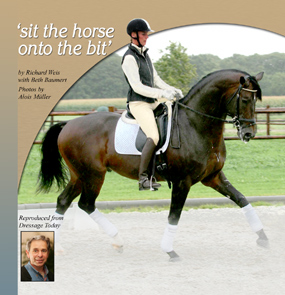

Photo caption:Imke Bartels ‘sits her horse on the bit’.

Her body is committed to a vertical planerelated to the ground. The horse

is contained and directed between her weight and the ground. Rhythmic

impulses from her body empower the aids and direct the horse.

Richard Weis

An Australian dressage coach and horse trainer, Richard was Sally Swift’s

first Centered Riding apprentice and is an Alexander Technique instructor.

His regular clientele includes the National Equesterian Federation of

Germany, the Netherlands, Australia and New Zealand as well as Olympians

and Paralympians.The Germans have written, mulled over and rewritten equestrian

scholarship countless times over the centuries, and they have come up

with a tiny but extraordinary passage that I found in the German Equestrian

Federation’s handbook, The Principles of Riding: “A correct

seat, of itself, acts as a positive influence on the horse’s movement

and posture because of the relaxed elasticity of the rider’s spine

together with the deep seat and soft embracing leg contact, are stimulating

the horse’s back movement and impulsion. The rider seems literally

to ‘sit the horse onto the bit,’ creating and maintaining his

desire for free, forward movement. Thus the rider is able to control the

horse and to keep the elastic ‘spring’ in all paces, even in

collection.”

This little spark of information landed in my head, and I couldn’t

get rid of it. I especially like the part that says: “The rider seems

literally to ‘sit the horse onto the bit,’ creating and maintaining

his desire for free, forward movement.” That’s a big statement,

because it clearly puts the responsibility for communication with the

horse on the seat of the rider. The seat is not there for aesthetics.

Rather, it functions in relation to it’s job of ‘sitting the

horse onto the bit’ and creating and maintaining the horse’s

desire for free, forward movement. The purpose of this article is to explain

how the seat of the rider mechanically does that job.

To understand how the rider sits the horse onto the bit, we must look

at the elements of the German Training Scale - the perfect diagnostic

model for what goes right and wrong in training. The Training Scale tells

us that the horse has to move with rhythm, elasticity, a correct connection

to the bridle, impulsion, straightness and collection. It is the rider’s

seat and back, in synchrony with the horse’s body, that communicates

or injects those qualities so the horse can move with appropriate coordination.

The degree of the dressage horse’s coordination requirements go far

beyond the normal call of duty for a horse. It’s not the way he would

trot across the paddock to get a drink. It’s the way he learns the

art of using himself in a way that carries a rider graciously. Dressage

excels above all other equestrian sports in the horse’s desire to

buoy up his rider, carry him and be available for his rider’s every

whim.

Understand Posture and Containment

Riders use themselves in a vertical plane, and horses use themselves in

a horizontal plane. The transference of information between horse and

rider happens at that right-angular junction where the vertical spine

of the rider connects to the horse’s horizontal spine - the point

where the rider’s seat meets the horse’s spine.

This relationship leads to the key concept that I wish to convey: The

rider needs to be aware of stacking up his body parts so he can maintain

his vertical posture and relate it to the ground for information he needs

for coordination and balance. Only then can the rider give his horse a

feeling of containment and elastic direction balanced between the rider’s

body weight and the ground.

That is phenomenally important because most riders end up feeling like

a victim of the horse’s movement - held up off the ground and weakened

by a lack of connection to the ground. Then the horse gets the impression

that he’s bouncing his rider around on the dressage arena. We have

to keep reminding ourselves that although he is big, we can convince him

that he is contained - I’m not above using the word ‘trapped’-

between our body weight and the ground. The Germans hate it when I use

the word ‘trapped’, so I assume it means something terminal

in the German language. I love the sense that there is nowhere for the

horse to go other than within the supple parameters of the rider’s

aids. The rider forms an elastic containment within his seat, back, driving

aids, the earth and the bit. When the horse is elastically connected and

contained between the body weight of the rider and the ground, the rider

is better equipped to feel the oscillations that are characteristic of

each gait and each movement.

Feel the Impulses and Oscillations

Every gait and movement of the horse has coordinating oscillations that

flow through the horse’s back, ribs and every joint in his body.

The canter half pass, for example, has its fundamental canter oscillations,

but it also has deflections that take him off the straight path and create

the direction and bend of the half pass. A sensitive, listening rider

can learn to feel these oscillations in order to create the timing and

direction of the aids that control his horse. When the rider learns to

feel this, his aids are automatically given in rhythm.

Impulses from the rider’s body direct the horse in rhythm, which

is the underlying element of the German Training Scale. The Training Scale

implies that if a horse doesn’t have rhythm, then he does not have

anything else going for him. He can’t be supple, he won’t be

able to seek contact with the bridle, and there will be no way of containing

any impulsion that’s put into him. This very simple point makes us

look at the rider’s responsibility for maintaining the evenness of

the beat. Since we always want to pay attention to the natural rhythm

and tempo for each horse, how do we know what is the best beat? It is

the one in which the horse is most able to swing his back, which leads

to the second point in the Training Scale - elasticity or suppleness.

The swinging hip and leg of the rider in the beat of the pace flows through

the back and belly of the horse through unblocked joints to the horse’s

feet. That rhythmic and supple connection can pick up and put down the

horse’s feet. That may sound like an overstatement, but it’s

a safe overstatement. The rider can learn the information he needs to

know so he can pedal (like a bicycle) through his pelvis and legs in order

to control the legs of his horse.

Pedal a Supple Rhythm

Ninety percent of equestrian literature regarding the aids talks about

specific, isolated pressures. The rider is asked, for example, to squeeze

or tap inwardly toward the horse with his leg. I don’t think that

a series of simple squeezes or taps with the leg can produce a regular

rhythm in a horse. Those specific aids are very secondary to the rider’s

ability to use his whole body to communicate to the horse in rhythmic

impulses.

The effective rider uses impulses of his own body weight to empower the

aids. His body is vertically ‘stacked up’ and grounded to the

earth. That vertical weight of the torso sinks down through the hip joint,

knee and calf and encourages the oscillations of the horse’s ribs.

Body weight stacked over a sitting bone allows the sitting bone to be

able to sink into the oscillation of the horse’s back.

A useful analogy is to imagine going up a hill on a bike. You’re

always using your weight to push the pedals down. There’s a ‘standing

downness’ that’s what I call part of ‘pedaling.’ You

can even get up off the saddle of the bike and jump your weight into the

sinking leg. (Later, we will refer to this as the specific moment of ‘stamp-down.’)

While pedaling, it would be idiotic to use the foot that’s closest

to the ground to lift the pedal upwards, but that’s what many people

do in trying to communicate with the horse. They pull the leg up and immediately

have no access to their own weight aids. Instead, they use muscular effort,

which causes the rider’s lower back, the pelvis and sitting bones

to lock. Then the squeezing or tapping leg is saying, “Go” to

the horse, but the seat is saying, “stay where you are.” The

rider’s back is blocked while he’s trying to unlock the horse’s

ribs, where the tension is great.

Ideally, the rider is like a spring. As he sits on the horse, he springs

impulses of pedalling weight downward, and he hopes to get a response

from the horse in the very next second that will buoy them up more. Then

he has to be ready to spring with the next impulse. The rider goes up

in order to go down and goes down to go up. (Of course, walk doesn’t

have that quality because there’s no suspension, but trot and canter

certainly have it.)

Riding is a buoyant activity. Listening well to the horse is a fairly

big part of what we need to get the horse to buoy us up on a cushion of

air, rather than banging us down to the ground like a bag of gravel. Impulses

that go down get received at that junction point of the seat and the back

and then need to flow up through the rider’s backbone and up through

the top of his head. For me, it feels like I lift the top of the horse

with the top of my head.

At this point, it is important to mention a fundamental rule of horse

training: A little bit from the rider should mean a lot to the horse.

It is not necessary to turn into a jackhammer in the name of promoting

rhythm. According to the Training Scale, once your horse has rhythm and

suppleness, you ask his body to lengthen longitudinally (from head to

tail) to fill the space up to the bridle, to seek the bit and to establish

contact.

The rider also stretches with a relaxed, elastic spine as he concentrates

his forces vertically. This toned quality gives him strength. ‘Toning’

is about dynamism of lengthening in a spring-like activity, and it occurs

in any vertebrate, whether it is that of a dressage horse or a human.

A toned body has positive tension. This is expressed in German as Spannung.

Somewhere between tense and loose is well organises Spannung. Positive

Spannung is the minimum effort necessary that will be distributed equally

while lengthening.

The rider’s legs work as shock absorbers, because the connection

from the torso of the rider through the legs to the stirrups has the tonal

quality that allows the rider to distribute some weight down to the stirrup.

If the rider’s pelvis synchronizes with the horse’s back and

oscillations from the rider’s lengthening backbone go down through

the knees and ankles, then we have shock-absorbing capacity in the legs.

We have the potential to distribute weight wherever we need it - in the

deepest part of the saddle, in the stirrups, in the front of the saddle

or wherever. We also have a positive situation in which the rider’s

body is acting as a spring in one piece and can be made more dynamic according

to the requirements of the horse or the movements that we’re trying

to ride.

Toning the Body Equals Suppleness

The next element of the German Training Scale is impulsion, with which

we ask a great deal more energy to be expressed through the body of the

horse in ‘nothing but movement’. That is, the horse expresses

himself in a supple rhythm, with postural organization such that he is

not wasting any energy in tension.

When the rider’s back is lengthened and toned, he can sit on a Quarter

Horse jog trot, but if he used the same relaxed, elasticity to sit on

Ulla Salzgeber’s Rusty going across the diagonal in extended trot,

he’d be in flopping chaos. The stronger the postural demand of the

movement, the more postural resources the rider’s body needs. Extraordinary

rider posture, enhanced by lengthening and toning of his body allows the

rider to relate to the ground for information regarding coordination and

balance so he can lead his horse more dynamically - even in more powerful

movements.

When the rider loses his vertical alignment, there can be no relaxed elasticity.

There can be no impulses of movement flowing down and through the bodies

of horse and rider. The postural challenge becomes too great, the rider

stiffens and tightens and, subsequently, is unable to recover the balance

and elasticity.

Timing and the Stamp-Down

As we continue to go through the Training Scale, we find that the next

element- straightening - involves longitudinal and lateral (bending) skills.

Every horse has a short and a long side. By bending one way and bending

the other - that is, by accentuating the swing of the horse’s ribs

toward the opposite shoulder systematically left and right, the short

side gradually becomes stretched and the long side learns to contract

until no bias remains. The rider bends his horse by distributing impulses

of weight a bit more down the inside of the horse in the timing and the

direction of bend.

The timing is what I referred to earlier as the ‘stamp-down’

moment. As you pedal downward, your timing will always be in coordination

with your horse. The bending aids should begin as the hind leg comes off

the ground and is coming forward - never when it’s on the ground.

If you can feel the movement of the downward impulse - the stamp-down

moment - you would never get those aids wrong, because the belly of the

horse is shifting off the hind leg that’s coming forward. If you

pedal upward, you’ll be doing it in your own timing, which won’t

necessarily suit the horse’s ability to respond to you. The direction

of bend is towards the position of the horse’s outside shoulder,

so impulses of the sitting bone and the calf go in this direction in order

to create bend.

The Postural Attitude for Collection

The final element of the Training Scale is collection. This is our ultimate

goal in dressage - to transfer weight from the front of the horse the

back of the horse and thus lighten the forehand so he is more manoeuverable.

This requires that the horse sit a little. This becomes sensationally

interesting from the rider’s point of view.

The rider has developed a toned quality of strength that makes him into

a kind of a lever. The vertical potential for leverage on the horse’s

back can rock weight back onto the hind legs because of the restraining

aids. If the rider concentrates his weight very vertically by bringing

his back toward his hands, it nearly straightens the hip joint. The Germans

call this bracing the back.

• Energy goes down the front of the rider’s thigh, then the

knee rotates back and down under the rider’s seat and the energy

comes down the back of the calf. The rider gets an experience of stretch

in which his body makes as close to a straight line as it ever gets.

• The lower back expands and comes behind the sitting bones that

continue to point toward the ground. He does a kind of shove up the front

of the saddle.

• The entire back of the rider goes toward the hands, and the weight

gets concentrated more vertically through the head of the femur and down

to the knee.

• The ankle is free so as soon as the knee starts to sink, the heel

will also sink.

The horse is being told: “I’m asking you for more energy, and

I’m asking your hind legs to come more forward and be more lively,

but I’m asking your front end not to run away while you do it.”

Through lengthening, the rider keeps the way open for the horse to channel

his effort upward. This intensely vertically aligned posture is the attitude

of collection. Every time we half halt, every time we ride a downward

transition, every time we prepare to come through a corner and have an

opportunity to get the back legs a little bit more under in collection,

we use this postural attitude of collection. Ultimately, it is the postural

attitude that rides piaffe.

Once the rider masters the ability to incorporate each element of the

Training Scale into his own way of moving, he can bring his horse along

and show him the way. Train yourself to do with your own body what you

would like your horse to do. Then you can literally ‘sit your horse

onto the bit,’ creating and maintaining his desire for free, forward

movement. Along the way, if you remember that a little bit from you should

mean a lot to your horse, you can’t go too far wrong.

Article reproduced with kind permission of Dressage Today magazine.

All International subscriptions to Dressage Today are $31.95 ($US) for

12 months or $55.95 for 24 months. For easy access, subscriptions can

be made online through a secure site at:

https://www.dressagetoday.com

or you can just visit their website to see the extensive range of articles

on training topics and international dressage trainers and competitors. |