|

A Readers Story

When its Wobblers... Hugo's Story

by Penny Lee

When Wobblers was first suggested as a diagnosis this owner did everything she could to give her young Warmblood a fighting chance, but sometimes fate decrees that no matter how much you do, it will not change the outcome.

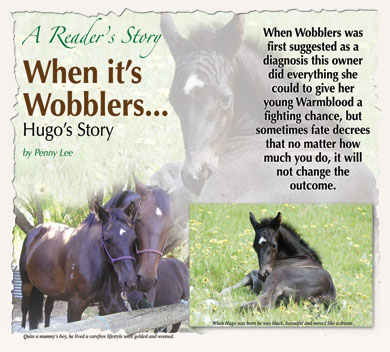

In 2006 my Warmblood mare gave birth to a foal that was everything I dreamed of: – black, beautiful, sweet temperament, lovely movement. I called him Hugo.

Apart from an umbilical cord infection at five days old, which quickly cleared up after veterinary intervention, Hugo lived the usual carefree life of a foal, with his mother and auntie doting over him and allowing him to chew their tails to shreds.

Weaning and gelding was put off for some time as he was quite a mummy’s boy and not as independent as the filly we had bred the previous year. Eventually gelded and weaned with no problem at all, he was sent off to live with other youngsters on a friend’s farm. However, a mild colic and ligament injuries to both back fetlocks saw him come home again after a few weeks. As with most youngsters the ligaments healed quickly. Tall and leggy with a long and elegant well- muscled neck, he was only 10 months old with lots of growing going on. Within two months you would not have known he had incurred the injuries; the swelling was gone and he was 100% sound.

By spring, while his legs were still fine he was however bark chewing badly and occasionally displayed very mild colic symptoms. He could be seen lying down for quite long periods in the shade and, when checked, would seem a bit depressed but had good gut noises and was eating well. One evening this changed and he was clearly much worse, so next day was floated to a vet hospital where they would be able to scope his stomach.

As suspected, they found ulcers – but the severity astounded the vets. Hugo had ulcers as bad as any they had seen in racehorses in full work. As he had always lived in good quality grass paddocks, with lucerne and meadow hay when needed and was not hard fed, everyone was amazed. The vets certainly could not account for it, but the severity of the ulcers meant he stayed at the vet hospital for over two weeks. When he came home we were astonished at how dreadful he looked. His ulcers were obviously heaps better but he was walking very strangely - crossing his back legs and appeared to have great difficulty getting his head down to eat. It seemed to us that there was something wrong with his neck.

The hospital had mentioned an incident with a post and rail fence – apparently he’d jumped it in a panic when a bull was put in the paddock next door, but they said he was fine with no major damage. After x-rays at the vet hospital it transpired that Hugo had been sent home with a fracture to his C6 spinal process. The crossed hind- leg walking was caused by the amount of inflammation in the area of the break pressing on his spinal cord. This way of walking is known as being a Wobbler.

The vets explained there are two main causes of wobbler’s syndrome, trauma or genetic predisposition (CSM). Wobbler’s from a minor trauma injury can clear up of its own accord once the inflammation has died down and won’t recur. However more major trauma injuries, such as the one Hugo sustained, have a much higher risk factor. The broken bone may heal and calcify into the spinal canal, causing a pressure point on the spinal cord and permanent wobbler’s syndrome of varying severity. At its most severe the back legs become so wobbly that the horse cannot control them properly. In this case a wobbler’s horse can become a danger not only to itself but also to its handlers, as they can trip, stumble and sometimes fall.

The condition causes no pain, but there is also no cure. Wobbler’s from genetic predisposition is called cervical stenotic myelopathy (CSM). It is a developmental orthopaedic disease (DOD) more commonly found in certain breeds such as Thoroughbreds and Warmbloods. Simply put, the spinal canal is found to have been formed with too narrow a space to accommodate the spinal cord, which becomes pinched, and the pressure causes wobbler’s syndrome. Once again this is completely painless.

I will never forget standing by the screen showing Hugo’s X-rays; the break to his spinal process was clear and there was some hope that it would heal without calcifying into the spinal canal. But we received a double whammy that day; they had measured the spinal canal ratios in his whole neck from the x-rays, and his ratios were too low. Hugo had wobbler’s from his trauma, but he was also considered 90% certain to develop CSM, if he had not started to develop it already.

We took Hugo home and adopted a feeding and management regime recommended by the hospital in relation to his trauma injury and possibly concurrent CSM. This followed research done at the University of Pennsylvania, where they had succeeded in curing CSM in foals between the ages of seven and twelve months. Hugo was a bit under 13 months old at the date of his injury – time was not on our side, as the regime is aimed at preventing growth spurts and he was already tall and leggy.

For nearly three months we devoted ourselves to Hugo’s care. His movement was restricted to a yard for most of the day where he had free access to hay. The rest of the time he grazed, to enable his neck muscles to strengthen and stretch normally. He was happy in the yard and he always had another horse for company. His feeding regime required a restricted diet – he basically needed to stay lean and slow his growth, and to increase his Selenium, Vitamin E and Vitamin A intake. Youngsters heal quickly, so once the initial inflammation from the break wore off he was happier; he could lower his head to graze without much difficulty and could roll in the sand patch, happily flipping from side to side like any other youngster. He was only slightly uncoordinated for a few days after arriving home and within days his legs no longer crossed at all.

As his favourite paddock game was to leap into the bonfire heaps and double barrel the leafy branches, there was no doubt he clearly knew exactly where his legs were and had complete control of them. To handle he was always a model patient, calm, quiet and trusting. By January 2008 Hugo was over 15 months old, with no sign of wobbling. We thought we’d done it – he was going to be all right. Then a few days later we found him lying down like a dog with his front legs out straight as he struggled to get up – it took six tries before he staggered to his feet. As he walked off it was evident he was in no pain and was perfectly relaxed in his paddock with his mates, but his back legs were crossing so badly he could not walk in a straight line. He reeled as though his back legs were barely connected to his body. The Wobbler’s had kicked in.

We did not know if the broken bone had calcified into the spinal canal or if it was the CSM finally showing itself. What we did know was that there was no future for him; now we had to free him from a life of vulnerability and confusion, where pain from future injury was going to be an absolute certainty. Whether helpful for others or not, this story certainly demonstrates that breeding can have pitfalls of which you have never dreamt. We were unlucky – some things you can’t beat, no matter how much you do or how hard you try. Hugo is buried in our back paddock under the trees where he most liked to doze. Anyone who has lost a loved horse knows the pain and heartache but it was especially hard to lose a horse so young, so beautiful and so trusting.

|