|

Watching the Portuguese School of Equestrian Art (Escola Portuguesa Arte Equestre) training day to day at the National Palace in Queluz, Lisbon, it is possible to see sixteen stallions working quietly together under the guidance of true horsemen, no shouting, no voice commands, no whips being used other than in guidance, no overuse of spurs - all in pursuit of one thing – for the rider to become ‘at one’ with each horse and for the horse to attain true, self-carriage.

The youngest, least experienced rider at The School learns from the experienced horse. The experienced rider teaches the young, inexperienced horse.

If the classical training principles of the School of Equestrian Art - the way international trainer Frederico Saramago was taught and is also passing down to his children - were echoed, horse owners of today would spend the first year working their horse on the lunge and with short lines on the ground. Re-balancing the horse to work from the hindquarters in preparation for the arduous task of carrying a rider and teaching it the foundations it needs before it ever has a rider on its back.

Today, however, trainers such as Frederico have had to adapt their teaching methods to the realities of the 21st century and are regularly working with horses that have never experienced the luxury of the solid, Classical foundation as a start to their training. They are often faced with riders, who are trying to learn and teach their horses at the same time.

There are of course exceptions, such as those involved in the riding schools of the world where Classical principles are adhered to, those such as Frederico’s children or individuals who have either the time, disposable income or access to an experienced trainer to guide them. These Classical principles that have been tried and tested through the ages are about creating a good foundation for both horse and rider and even if, in this modern day society, many riders are limited by lack of time, the foundation will create a solid base towards horse and rider working together as one, but just as importantly, with the horse working happily with a well balanced rider on its well balanced back.

Training circles are just a small section of a whole training aspect that is difficult to isolate without readers first having an understanding of the Classical Horsemanship foundations.It may however give them a taste for the art of working their horse towards a level of education and consequently obedience and, most importantly, safety. And from there to progress to higher ideals.

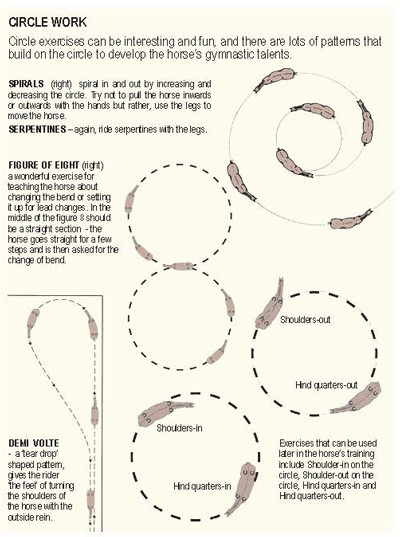

RIDING Circles

Riding circles and straight lines can be seen as accuracy, obedience and gymnastic tools that can be used to achieve the best from a horse’s training session. There’s no reason riders should bore a horse with endless 20 metre circles and circuits of an arena when each training session can be made interesting and can capture the horse’s mind. Almost endless patterns are available that will allow circles to be used as an aid to creating balance and rhythm.

The majority of all riding is done on curving paths - circles or parts of them - with a laterally bent horse. Of all the patterns, the most important is the circle and when it is ridden correctly it is the consequence of precise, even bending, while in motion. And perhaps the key to achieving this is in the words of Frederico Saramago, “Inside leg to outside rein”.

On-line Lunging

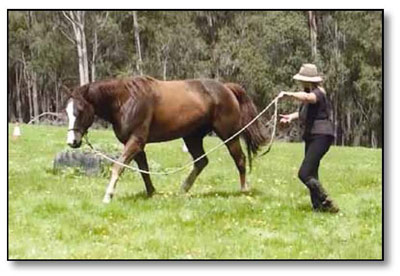

Circles can be started when the horse is at a very young age, firstly using a rope halter, and a single 3.65m (12ft) line. Balance for a young horse is more precarious, particularly when a human is attached to the end of the line. A rope halter has more feel than a traditional halter and can be light when required or strong if needs be. For a larger horse a 6.7m (22ft) line can be used. If working with a stallion or a more dominant horse that has learnt to pull away or rush forward then a cavesson will allow the handler extra control. Great care should be taken if a bridle is used for circle work on the lunge and it should only be used with a horse that understands totally what is expected of it, as damage can be inflicted to its mouth.

Initially the young or ‘green’ horse may not perform an accurate round circle - it may come in closer on one side of the circle and lean out on the other - usually towards its mates in the paddock or even the arena gate or the stable. For example, a horse on the lunge with its head bent to the outside, falling on its inside shoulder and zooming around like a motorbike will gain nothing from such a session. Therefore, it is important to correct the horse’s frame in order to achieve a quality circle.

The way to combat the problem is to close the hand on the lunge if the horse is leaning out and hold. As soon as the horse gives to the hand then relax and open the hand again. When the horse falls into the circle, the whip or stick can be pointed at its shoulder and once again removed to a neutral position as soon as it responds. Free lungeing is an exercise that can be beneficial for the horse when the handler is experienced but is not something that the inexperienced person should attempt.

The correct head position of the horse, either ridden or on the lunge line, requires the poll to be the highest point, the face should be at or slightly in front of the vertical and the horse’s ears level, even when its head is turned. The only time this would be different is if the rider/handler is encouraging the horse to stretch ‘long and low’.

These lunge sessions can be interesting for handlers as they can learn a lot about their horse’s character, capture its mind and build trust and communication when the sessions are tailored to suit each horse i.e. if a horse has a tendency to ‘run off’ then work it more slowly with more changes of direction, if another gets bored – do the circles in a big paddock and introduce obstacles such as cavalettis, poles on the ground or witches hats, around which the horse can be manoeuvred. The rider/handler needs to maintain the interest of the bored horse whilst with the impulsive horse the need is to build trust and confidence through repetition.

Play with changes of gait and tempo and lots of changes of direction. Use a stick or whip pointed at the girth area to create ‘the bend’ required for a circle. The stick should be used in the same manner as a leg aid would for the ridden horses - ‘pressure on, pressure off’ – and the second the horse reacts to the stick by moving out or bending, then the ‘pressure’ (or pointing stick) should be returned to a neutral position. Play with the horse and see what works for this individual – with very sensitive horses, a response can often be achieved when the handler just looks at the girth area or any area they might like to influence. The constant changes of tempo, gait and direction will all work together to help keep the horse’s attention focused on the handler and not on what’s happening outside the lunge area. If this is done well it will then create a solid foundation for achieving good circles when ridden.

Side reins are an option to be used only on rare occasions and only under expert guidance as, incorrectly used, they can create more problems than they fix.

RIDING CIRCLES

Circle work begins in the arena, or a level spot in the paddock, ideally measured out to 40m x 20m or 60 x 20m with markers or letters to help both horse and rider focus and direct their energy. If the rider is not focused then the horse is not going to be. A marked area also gives purpose to the so-called lazy horse, whose attitude can be changed when it feels it is being ridden with purpose and is ‘going-somewhere’ when the rider uses the markers as indicators for exercises and patterns. This also prevents the more extrovert horse from taking over and making the exercise a bit more interesting for itself! Markers or letters as points of reference are invaluable in the development of the horse’s athletic and gymnastic ability – they encourage the rider to ride with focus, intention and precision and help monitor the horse’s level of education and consequently obedience. Regardless of the chosen discipline, obedience is a quality for which all riders should strive - for both safety and enjoyment.

The circle is best ‘visualised’ by the rider and not drawn in the sand or marked out, as this can result in the rider leaning over to check the lines, as even just leaning their head to one side or looking down can result in a shift of five to six kilos - that’s without the weight of their body that will follow the head either forward or sideways. Not only will this affect the rider and the horse’s balance, it will make it impossible to ride a ‘true’ circle, no matter how wonderful the ‘inside leg to outside rein’ contact. This is especially the case with the more sensitive horse. Riders should imagine how five bags of sugar, carried in one hand, would affect the way they walked.

Start the circle in walk and allow the horse to do this at its own pace to start with. Don’t try to influence the horse by kicking, using the seat or pulling on the reins – just mirror the horse’s movement. The so-called ‘lazy’ horse will walk infuriatingly slowly but if the rider ‘goes with the movement’ it may soon ‘offer’ more. A good walk comes from the horse’s mind and with that a relaxation of the body (schwung). One way to achieve a swinging walk from a slow horse is to ask it to walk a half or quarter circle much slower that it would like or was offering, using only enough leg to keep it going forward. This is using reverse psychology, as when the reins are given the horse will offer more forwardness.

So much about ‘working’ a horse successfully comes from ‘asking’ not ‘telling’ or worse, ‘micromanaging’ by kicking or tapping with the whip constantly, or even using the spur all the time without achieving the desired results.

With a more impulsive horse, start with a trot until the horse settles, then ask for very small (five metre) circles when trotting down the long side. Invite the horse to walk the short side – making the transition to walk at the last marker before the corner. The other option is – as Frederico calls it, ‘head to the wall’ – a basic travers. This slows the impulsive horse and gets it thinking.

One technique that works well in the teaching phase, is to place a drum in the centre of the circle and use that point as the ‘comfort zone’ when working the horse. As soon as the rider feels the horse is going forward willingly and softly, even if it’s only two strides, they allow the horse to stop and rest at the drum. Acknowledging the little ‘tries’, then allowing the horse to stop and rest at the drum will make it more willing next time it is asked to go forward. This can even help bend the horse, not only around the drum but also around the rider’s ‘inside leg’, which like the drum, is a passive pole around which the horse can bend (hypothetically). As the horse becomes confident and willing, the drum can be dispensed with, but visualise it when riding those circles. The rider should not turn their head, instead they should think of using their shoulders to turn their horse’s shoulders – without leaning or collapsing a hip - and their ‘outside rein’ as a stick on the horse’s neck. The ‘outside leg acts as a closed door – not pushing – just saying to the horse, “don’t go there”!

Feathering or vibrating the rein can be used to soften the horse’s jaw. For instance, the horse may be bending its neck too much to the inside so feathering or vibrating the outside rein is a reminder to straighten up a bit and is a good way to dissolve minor ‘one sided’ rein resistance.

But vibrating is most effective with the inside rein, which would be vibrated a little for more bend, or with a slight lift of the rein so the shoulder can be corrected. It also acts passively when the rider is thinking ‘inside leg to outside rein’.

The inside rein is not the rein to use for the turn and should NEVER be pulled back. When the inside rein is used the horse either turns like a semi-trailer or will swing its haunches to the outside. If, however, the outside rein is used on the horse’s neck then it will turn from the withers, which is more like turning a bus than a semi-trailer.

The most misused aid is the inside rein being pulled back and the most neglected aid is the outside leg - generally not used at all - especially in aiding the turn.

Good hands, whether working a horse on the ground or under saddle, give when the horse gives and take - hold, not pull - when the horse takes.

Gradually the horse will understand what is expected and the circles will improve in shape and consistency, then changes of gait and tempo and lots of changes of direction on the circle can be added to the horse’s training sessions.

If the horse or rider is having trouble riding a circle they can try riding a square to improve this. ‘The Square of La Gueriniere’ is a most valuable exercise and has been used since 1729! Do this exercise at the walk. At each corner of the square ride until the horse’s shoulders are just beyond, keeping the haunches on the corner and execute a turn on the haunches, without reversing, by turning the forehand onto the new line. This improves the control of the shoulders and the horse will then find circles easier.

The school figures should be practised equally on both reins to exercise and develop complete muscular structure, balance and ambidexterity (using left and right side equally) of the horse and then, only when the rider also becomes ambidextrous can the horse be expecte d to travel well. d to travel well.

The horse is relaxed, the swing in its back and tail is visible and it is bending on the circle. The handler has a feel on the lunge line, but no pull.

BUSH CLASSICAL RIDING

Arena work should be balanced with ‘outside’ activities, which build strength, bravery and aerobic ability in the horse.

It’s fun to try some ‘bush classical riding’ so make it a habit to ride as if in the arena when out on the trail, riding in the paddock or in the bush: circle around trees or bushes, weave through trees, logs or large rocks; the possibilities are endless and loads of fun and those with shying horses will find they suddenly shy less often, and bored horses become more interested and energetic.

Riders should always remember to ride in the arena as if they are outside and ‘going somewhere’ and ride outside as if they are in the arena, in terms of obedience and balance but not necessarily highly collected. It is good, both in the arena and outside, to allow the horse to stretch its neck and back regularly.

There is also a need to be aware that for everything riders say about the horse, the horse could be saying about them: Is the rider balanced and engaged? Are their shoulders leaning in or out? Are they on the forehand?

Those who are sincere about following classical principles would be eager to let the horses have their say. Not only would they be learning from the true masters, they would also become adept at working with the horse’s nature.

When riders discover the ‘conversation’ with their horse, the dance begins!

Or, as Frederico says, “For dancing the tango – we need two”!

|